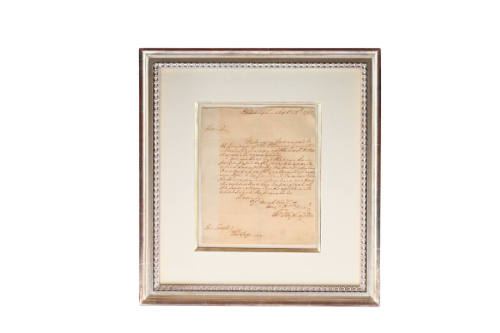

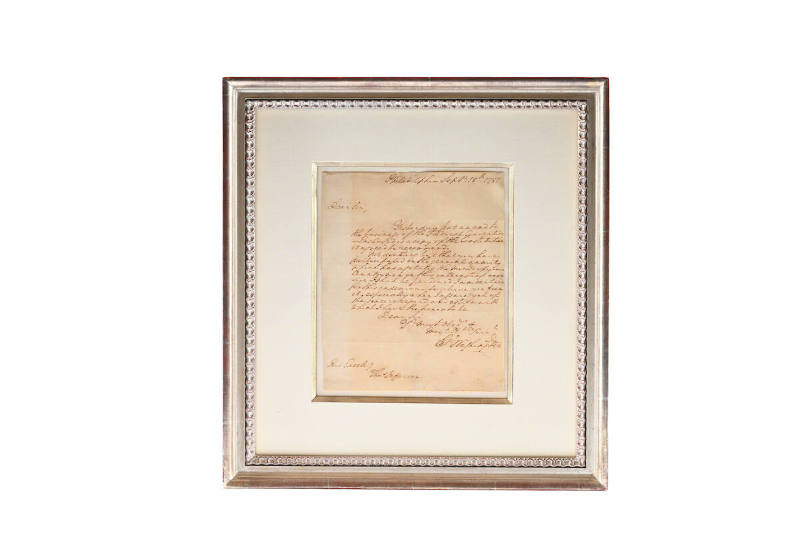

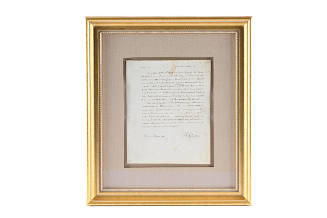

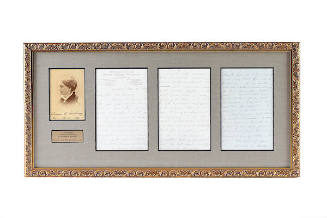

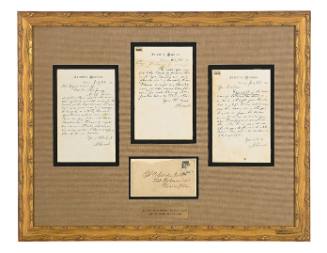

George Washington Letter to Thomas Jefferson, on the recommendation of the U.S. Constitution

Letter: 8 1/2 x 7 1/8 in. (21.6 x 18 cm)

The letter reads:

Philadelphia Septr. 18th. 1787.

Dear Sir,

Yesterday put an end to the business of the Foederal Convention – Enclosed is a copy of the Constitution it agreed to recommend.

Not doubting but that you have participated in the general anxiety which has agitated the minds of your Countrymen on this interesting occasion. I shall be pardened I am certain for this endeavour to relieve you from it, especially when I assure you of the sincere regard and esteem with which I have the honor to be,

Dear Sir, Yr. most obedt. & / Most Hble Servt

Go: Washington

His Excell(enc)y Thos Jefferson.

The day following the completion and signing of the Constitution by the Convention, George Washington sends Thomas Jefferson a personal letter announcing its adoption and enclosing a copy of the landmark document.

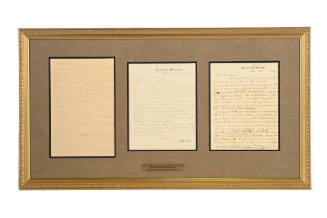

Jefferson had been a guiding voice of the Founding generation, but in 1787 he was in Paris serving as the United States Minister Plenipotentiary to France. He was thus absent from the proceedings that debated and drafted the Constitution in Philadelphia that summer. Since his arrival to France in 1784, he kept himself informed of events at home through his frequent communication with John Adams and John Jay and others. His correspondence, especially with his mentee James Madison, certainly influenced the Constitutional debates. However, with the delegates sworn to absolute secrecy when the Convention commenced on May 25, 1787, to Jefferson’s frustration, he was then left in the dark.

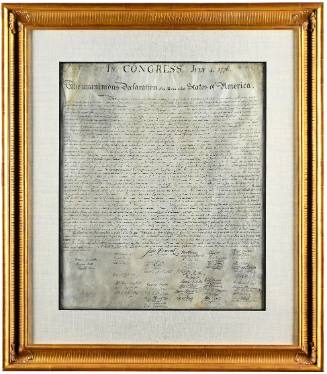

After four months filled with contentious debate, on September 17, 1787, the Convention completed their work and 39 delegates signed the engrossed Constitution. George Washington, as President of the Convention, additionally signed two cover Resolutions. The first resolved that the proposed United States Constitution be “laid before the United States in Congress assembled” (meeting in New York under the Articles of Confederation). It provided a succinct plan for the Constitution to be sent by them to the states for ratification, and upon ratification to implement the new Federal government by electing representatives, convening Congress, and electing the first president. The second was a transmittal letter to the Confederation Congress, acknowledging that every state would disagree with certain points of the document, but that compromise was necessary to secure the greater interests of all.

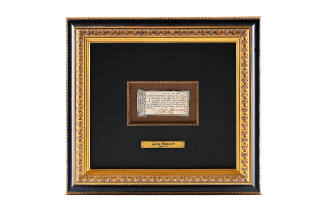

Together, the Constitution and the Resolutions were then immediately sent to Philadelphia printers Dunlap & Claypoole. By the next day, September 18, up to 500 copies were printed (only 13 of which are known to survive) for distribution to and by the delegates. The same day, the secretary of the Convention, William Jackson, got on the coach to New York to deliver a number of those imprints to the Confederation Congress.

Having himself just received several of the freshly-printed Constitutions, on the morning of the 18th, Washington wrote this letter to Jefferson. By personally sending one of the newly printed Constitutions including the covering Resolutions just a day after the Convention’s adjournment, Washington wanted to be the first to break the silence. However, this letter was inexplicably delayed; Jefferson did not receive it until December, and Washington expressed his mortification in his next letter, especially given his desire and intention to be the first to notify Jefferson of the new Constitution. In the meantime, Jefferson received additional copies of the Constitution from John Adams in London, and from Elbridge Gerry in Massachusetts.

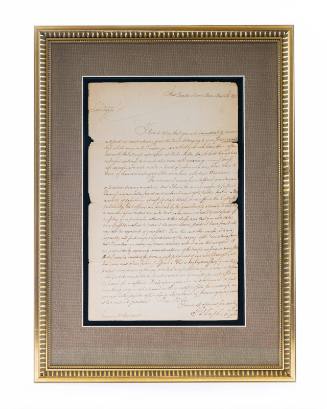

Washington sent only one other letter on September 18, 1787, to the Marquis de Lafayette, known only from the secretarial letterbook copy, in the George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress. Six days later, from Mount Vernon, Washington sent three more copies of the Constitution, with letters identical to each other in content, to Patrick Henry, Benjamin Harrison, and Thomas Nelson.

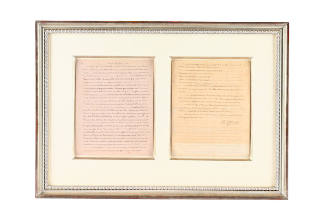

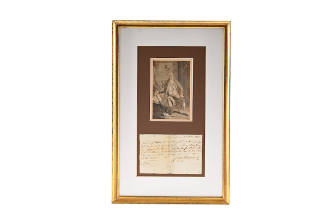

In 1815, schoolmaster Amos J. Cook asked Jefferson for a sample of his own and Washington’s handwriting. Jefferson obliged by providing this historic letter, accompanying his own excellent philosophical cover letter (see 2022.038.0001), though without its original enclosure. Unfortunately, we have not seen a hint of what became of the Constitution that Washington originally sent.

Cook put the Washington and Jefferson letters on display at the museum at Fryeburg Academy in Maine. When the building was destroyed by fire in 1850, both were assumed lost in the conflagration. They were rediscovered in 1902 among the papers of academy trustee Major James Osgood. The school reprinted both documents that year in the academy’s centennial tribute to Daniel Webster, a former Fryeburg preceptor, citing them as “golden links binding our venerable school to the Fathers of the Republic.”